SOMA – Significance and the activity of meaning(1985)

Extract from Chapter 3 of D. Bohm, Unfolding Meaning: A Weekend of Dialogue. ed. Donald Factor, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London U 19851, 1987).

In chapter[5, pp. 158-182 of Lee Nichol (2003) The Essential David Bohm, Routledge] Bohm outlines the nature of soma-significant and signasomatic activity. Here “soma” refers to the body, and by extension to any material structure or process, while” significance” refers to mind or meaning. These terms are meant to suggest complementary aspects of one indivisible process, rather than two qualitatively distinct domains. With this model Bohm furthers his argument that there is no essential difference between reciprocal processes in the objective world (Chapter 1 of Nichol) and reciprocal processes in the perception and cognition of human beings (Chapter 2of Nichol), suggesting that active meaning is enfolded and unfolded throughout the whole of existence. Soma-significant and signa-somatic processes are thus seen as aspects of the dynamics of implicate and explicate orders.

Two examples indicate the scope of soma-significant processes. In the human realm, a somatic form, e.g., a traffic light, presents a significance to a driver. This significance is developed throughout increasingly subtle somatic structures – the visual system, the nervous system, and the brain of the driver (a soma-significant flow). These levels of somatic subtlety have corresponding meanings, and a cumulative significance for the driver – in this case, “stop.” This significance becomes active, and the process then moves in an .outward” direction. The brain produces an intention to stop, which works its way out through increasingly. manifest” levels of soma – the nervous system and the musculature – resulting in stopping the car (a signa-somatic flow).

At the quantum level of matter, says Bohm, soma-significant processes also occur. In Bohm’s version of quantum theory (Chapters 4 and 6 of Nichol), a “pilot wave” reads the somatic form of the environment and conveys this form to its accompanying particle (a soma-significant flow). The subtler somatic structure of the particle – which Bohm suggests is at least as complex as a radio receiver – develops a cumulative ” orientational” significance from this information. When this significance is fully developed it also becomes outwardly active, giving rise to specific movements on the part of the particle (a signa-somatic flow).

For Bohm, the pilot wave model is not merely analogous to human soma-significance. He sees each of these examples as abstracted nodes in a continuum that includes the quantum level, the human domain, and the large scale evolution of the cosmos. As a magnet divided into multiple parts will always exhibit positive and negative poles in each part, so also will any aspect of reality we select for examination show somatic and significant aspects. It is not possible to find an independent somatic phenomenon, or an independent significant phenomenon. Anywhere we make a cut in the fabric of reality, we will find this mutual interpenetration of soma and significance.

The implication of this perspective is central to Bohm’s overall world view: meaning is not an exclusively human activity. We typically think of meaning as subjective attribution: “My wife means a lot to me.” “That was a meaningful conversation.” “What is the meaning of the universe?” The human mind is thus tacitly understood to be the exclusive source and repository for meaning. But Bohm’s model turns this view on its head, seeing human meaning as a particular case of active,

soma-significant meaning in the universe at large. From this perspective, we may have meaning for the universe. Further still, the universe may be meaningful to itself, with or without the presence of humans. A field of daisies, a cluster of galaxies, or the inner structure of an electron are understood as being actively engaged in soma-significant and signa-somatic processes. For Bohm the operative question and subsequent inquiry then becomes: How are our human meanings related to those of the universe as a whole? Lee Nichol

I want to introduce a new notion of meaning which I call soma-significance, and also a notion of the relationship between the physical and the mental. This relationship has been widely considered under the name psycho-somatic. “Psyche” comes from a Greek word meaning mind or soul and “soma” means the body. If we generalize soma to mean physical, the term psycho-somatic suggests two different kinds of entities, each existent in itself – but both in mutual interaction. In my view such a notion introduces a split, a fragmentation, between the physical and the mental that doesn’t properly correspond to the actual state of affairs. Instead I want to suggest the introduction of a new term which I call “soma-significance.” This emphasizes the unity of the two, and more generally, with meaning in all its implications and aspects. That is, “significance” goes on to “meaning,” which is a more general word.

In this approach meaning is clearly being given a key role in the whole of existence. However any attempt at this point to define the meaning of meaning would evidently presuppose that we already know at least something of what meaning is, even if perhaps only nonverbally or subliminally. That is, when we talk we know what meaning is; we could not talk if we didn’t. So I won’t attempt to begin with an explicit definition of meaning, but rather, as it were, unfold the meaning of meaning as we go along, taking for granted that everyone has some intuitive sense of what meaning is.

The notion of soma-significance implies that soma (or the physical) and its significance (which is mental) are not in any sense separately existent, but rather that they are two aspects of one over-all reality. By an aspect we mean a view or a way of looking. That is to say, it is a form in which the whole of reality appears – it displays or unfolds – either in our perception or in our thinking. Clearly each aspect reflects and implies the other, so that the other shows in it. We describe these aspects using different words; nevertheless we imply that they are revealing the unknown whole of reality, as it were, from two different sides.

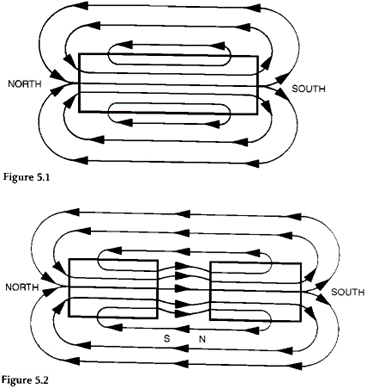

You can obtain a good illustration in physics for the unbroken wholeness underlying the aspects that are, nevertheless, distinguished, by contrasting the relationship of electrical poles or charges and magnetic poles. Electrical charges are regarded as separately existent and connected by a field; but magnetic poles are not that way. They are really one unbroken magnetic field. That is, if you take a magnet with a north and south pole, you may consider that there is a field going around the magnet from the north to the south pole. You may have seen this illustrated with iron filings (see Figure 5.1).

Now the point is that if you take this magnet and break it, you get two magnets, each of which has a north and a south pole (see Figure 5.2).

So you can see that there is actually no separate magnetic pole. In fact you may consider that even when it is not broken, every part is a superposition of north and south poles, and you may then understand the relationship as flowing.

With the aid of this concept of opposing pairs of magnetic poles, we can contribute in a significant way to expressing and understanding the basic relationships in the overall magnetic field. I propose to look at soma-significance in a similar way. That is to say, I regard them as two aspects distinguished only in thought, which will help us to express and understand relationships in the “field” of reality as a whole.

To bring out how soma and significance are related, I might note that each particular kind of significance is based on some somatic order, arrangement, connection and organization of distinguishable elements – that is to say, structure. For example, the printed marks on this piece of paper carry a meaning which is apprehended by a reader. In a television set the movement of electrical signals communicated to an electron beam carries meaning to a viewer. Modern scientific studies indicate that such meanings are carried somatically by further physical, chemical and electrical processes into the brain and the rest of the nervous system where they are apprehended by ever higher intellectual and emotional levels of meaning.

As this takes place, these meanings, along with their somatic concomitants, become ever more subtle. The word “subtle” is derived from the Latin sub-texere, meaning woven from underneath, finely woven. The meaning is: rarified, delicate, highly refined, elusive, indefinable, intangible. The subtle may be contrasted with the manifest, which means literally, what can be held in the hand. My proposal then is that reality has two further key aspects, the subtle and the manifest, which are closely related to soma and significance. As I pointed out, each somatic form, such as a printed page, has a significance. This is clearly more subtle than the form itself. But in turn such a significance can be held in yet another somatic form — electrical, chemical and other activity in the brain and the rest of the nervous system – that is more subtle than the original form that gave rise to it.

This distinction of subtle and manifest is only relative, since what is manifest on one level may be subtle on another. Thus the relatively subtle somatic form of thought may have a meaning that can be grasped in still higher and more subtle somatic processes. And this may lead on further to a grasp of a vast totality of meanings in a flash of insight.

This sort of action may be described as the apprehension of the meaning of meanings, which may in principle go on to indefinitely deep and subtle levels of significance. For example in physics, reflection on the meanings of a wide range of experimental facts and theoretical problems and paradoxes eventually led Einstein to new insights concerning the meaning of space, time, and matter, which are at the foundation of the theory of relativity. Meanings are thus seen to be capable of being organized into ever more subtle and comprehensive over-all structures that imply, contain and enfold each other in ways that are capable of indefinite extension – that is, one meaning enfolds another, and so on. So you can see that the meaning of the implicate order must be closely related. The implicate order is a way of illustrating the way meaning is organized.

In terms of the notion of soma-significance there is no point to the attempt to reduce one level of subtlety in any structure completely to another. For example, if you meet a certain content on one level and then on another, the relationship between these levels is the essential content of yet another level. So it is clear that no ultimate reduction is possible. As the level under consideration is changed, the particular content of what is somatic (or manifest) and what is significant (or subtle) has always therefore to be changing. Nonetheless it is clear that it is necessary for both roles to be present in each concrete instance of experience. You see, it is like the magnetic poles. Wherever you cut the magnet you have a North and a South pole, and wherever you make a cut in experience and abstract something, and say, “This is the experience” (which is a bigger context) you have soma-significance. It would be impossible to have all the content on the side of soma or on that of significance.

I have emphasized so far, the significance of soma – that is, that each somatic configuration has a meaning – and that it is such meaning that is grasped at more subtle levels of soma. I call this the soma-significant relation, which is one side of the over-all process. I would now call attention to the inverse, signa-somatic relation. This is the other side of the same process in which every meaning at a given level is seen actively to affect the soma at a more manifest level. Consider for example, a shadow seen in a dark night. Now if it happens, because of the person’s past experience, that this means an assailant, the adrenalin will flow, the heart will beat faster, the blood pressure

will rise and he will be ready to fight, to run or to freeze. However if it means only a shadow, the response of the soma is very different. So quite generally the total physical response of the human being is profoundly affected by what physical forms mean to him. A change of meaning can totally change your response. This meaning will vary according to all sorts of things, such as your ability or background, conditioning, and so on.

This is different from psycho-somatic, because with psycho-somatic you say that mind affects matter as if they were two different substances – mind substance affects material substance. Now I am saying there is only one flow, and a change of meaning is a change in that flow. Therefore any change of meaning is a change of soma, and any change of soma is a change of meaning. So we don’t have this distinction.

As a given meaning is carried into the somatic side, you can see that it continues to develop the original significance. If something means danger, then not only adrenalin, but a whole range of chemical substances will travel through the blood, and according to modern scientific discoveries, these act like “messengers” (carriers of meaning) from the brain to various parts of the body. That is, these chemicals instruct various parts of the body to act in certain ways. In addition there are electrical “signals” – they are not really signals – carried by the nerves, which function in a similar way. And this is a further unfoldment of the original significance into forms that are suitable for “instructing” the body to carry out the implications of what is meant.

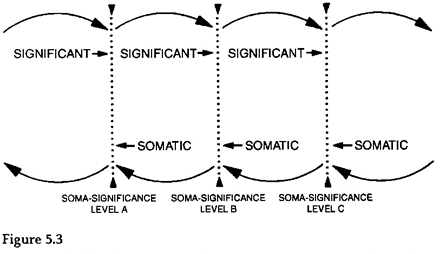

From each level of somatic unfoldment of meaning there is then further movement leading to activity on a yet more manifestly somatic level, until the action finally emerges as a physical movement of the body that affects the environment. So one can say that there is a two-way movement of energy in which each level of significance acts on the next more manifestly somatic level, and so on, while perception carries the meaning of the action back in the other direction (see Figure 5.3).

As in cutting a magnet it does not mean that these lines represent distinct levels; they are merely abstracted in our mind.

I want to emphasize here that nothing exists in this process except as a two-way movement, a flow of energy, in which meaning is carried inward and outward between the aspects of soma and significance, as well as between levels that are relatively subtle and those that are relatively manifest. It is this over-all structure of meaning (a part of which I’ve drawn in this diagram) that is grasped in every experience. We car see this by following the process in the two opposing directions. For example, as light strikes the retina of the eye, carrying meaning in the form of an image, the meaning is transformed into a chemical form by the rods and the cones. They in turn are transformed into electro chemical movements in the nerves, and so on into the brain at higher and higher levels. Then in the other direction, higher meanings are carried electrically and chemically into the structures of reflexes and thus onward toward ever more manifestly somatic levels.

I have been discussing what you might call the normal soma significant and signa-somatic process. Usually psycho-somatic processes are discussed in terms of some disorder, and you can see here that you can also get signa-somatic disorder. For example, normally the heart will beat faster when something means danger. One realizes that that is the signa-somatic response to the meaning of danger. But it could also mean that something is wrong with the heart, in which case the danger will be indicated by the rate of the beating of the heart. In that case every time the heart beats faster it fills the person with more of the meaning of danger and causes the heart to beat faster still. So you get a runaway loop, and that could be an important component of neurotic disorders the normal process gets caught in a loop that goes too far.

You can see that ultimately the soma-significant and signa-somatic process extends even into the environment. Meaning thus can be conveyed from one person to another and back through sound waves, through gestures carried by light, through books and newspapers, through telephone, radio, television and so on, linking up the whole society in one vast web of soma-significant and signa-somatic activity. You can say society is this thing; this activity is what makes society. Without it there would be no society. Therefore communication is this activity.

Similarly even simple physical action may be said to communicate motion and form to inanimate objects. Most of the material environment in which we live – houses, cities, factories, farms, highways, and so on – can be described as the somatic result of the meaning that material objects have had for human beings over the ages. Going on from there, even relationships with nature and with the cosmos flow out of what they mean to us. These meanings fundamentally affect our actions toward nature, and thus indirectly, the action of nature back on us is affected. Indeed as far as we know it and are aware of it and can act on it, the whole of nature, including our civilization which has evolved from nature and is still a part of nature, is one movement that is both soma-significant and signa-somatic.

Some of the simpler kinds of soma-significant and signa-somatic activity are just reflexes that are built into the nervous system, or instincts that express the accumulated experience of the species. But these go on to ever finer and more variable responses. Even the behaviour of creatures as simple as bees can be seen to be so organized in a very subtle way by a kind of meaning, in this case through a dance indicating the direction and distance of sources of nectar. Though they might not be conscious of it, there is a meaning going on. With the higher animals this operation of

meaning is more evident, and in man it is possible to develop conscious awareness, and meaning is then most central and vital.

In these higher levels this soma-significant and signa-somatic activity shows up most directly. In fact the word “meaning” indicates not only the significance of something to us, but also our intention toward it. Thus “I mean to do something” means “I intend to do it.” This double meaning of the word” meaning” is not just an accident of our language, but rather it implicitly contains an important insight into the structure of meaning.

To bring this out I would first note that an intention generally arises out of a previous perception of the meaning or significance of a certain total situation. This gives all of the relevant possibilities and implies reasons for choosing which of these is better. Ultimately this choice is determined by the totality of significance at that moment. The source of this activity includes not only perception and abstract or explicit knowledge, but what Polanyi calls tacit knowledge — that is, knowledge containing concrete skills and reactions that are not specifiable in language, such as riding a bicycle.

Ultimately it is the whole significance that gives rise to intention, which we sense as a feeling of being ready to act in a certain way. For example, if we see a situation meaning “the door is open,” we can form the intention to walk through it, but if it means “the door is closed,” we don’t. But even the intention not to act is still an intention. The whole significance helps to determine it. The important point is that the intention is a kind of implicate order; the intention unfolds from the whole meaning. It doesn’t just come out of nothing. Therefore a person cannot form intentions except on the basis of what the situation means to him, and if he misses the mark on what it means, he will form the wrong intentions.

Of course, most of the meaning is implicit. Indeed, whatever we say or do, we cannot possibly describe in detail more than a very small part when such significance gives rise to an intention, it too will be almost entirely implicit, at least at the beginning. For example, as I said, I have an intention to speak at this moment, and it is implicit what I am going to say; I don’t know what I’m going to say exactly, but it comes out. Now the words are not chosen one by one, but rather are unfolded in some way.

Meaning and intention are therefore inseparably related as two sides of aspects of one activity. This the same as we discussed with soma and significance, and the subtle and the manifest. We are saying that there is one whole of activity abstracted at a certain point conceptually — we make a cut in it – and we say it always has two sides. One of the two sides is meaning, and the other would be intention. But they don’t exist separately.

Intentions are commonly thought to be conscious and deliberate. But you really have very little ability to choose your intentions. Deeper intentions generally arise out of the total significance in ways of which one is not aware, and over which one has little or no control. So you usually discover your intentions by observing your actions. These in fact often contain what are felt to be unintended consequences leading one to say, “I didn’t mean to do that. I missed the mark.” In

action, what is actually implicit in what one means is thus more fully revealed. That is the importance of giving attention.

To learn the full meaning of our intentions in this way can very often be costly and destructive. What we can do instead is to display the intention along with its expected consequences through imagination, and in other ways. The word “display” means “unfold,” but for the sake of revealing something other than the display itself. As such a display is perceived one can then find out whether or not one still intends going on with the original intention. If not, the intention is modified, and the modification is in turn displayed in a similar way. Thus to a certain extent, by means of trying it out in the imagination, you can avoid having to carry it out in reality and having to suffer the consequences, although that is rather limited.

So intention constantly changes in the act of perception of the fuller meaning. Even perception is included within this over-all activity. What one perceives is not the thing in itself, which is unknown or unknowable, but however deep or shallow one’s perceptions, all one perceives is what it means at that moment, and then intention and action develop in accordance with this meaning.

The point is that as you act according to your intention, and as the perception comes in, there can arise an indefinite extension of inward signa-somatic and soma-significant activity. That is, you go to more and more subtle levels and the thing is, as it were, looking at itself at different levels ever more deeply.

Such activity is roughly what is meant by the mental side of experience. When something is going on that is not strongly coupled with the outer physical manifestation of some soma-significant and signa-somatic activity in which it is looking at itself, then we call that the mental side of experience. Now this is only a side. Once again I want to repeat that there is no separation between the mental and the physical. When it gets to the other side where it is primarily concerned with actions it just gets more physical.

Now we can look at this in terms of the implicate or enfolded order, for all these levels of meaning enfold each other and may have a significant bearing on each other. Within this context, meaning is a constantly extending and actualizing structure — it is never complete and fixed. At the limits of what has at any moment been comprehended there are always unclarities, unsatisfactory features, failures of intention to fit what is actually displayed or what is actually done. And the yet deeper intention is to be aware of these discrepancies and to allow the whole structure to change if necessary. This will lead to a movement in which there is the constant unfoldment of still more comprehensive meanings.

But of course each new meaning has some limited domain in which the actions flowing out of it may be expected to fit what actually happens. These limits may in principle be extended indefinitely through further perceptions of new meanings. But no matter how far this process goes there will still be limits of some kind, which will be indicated by the discovery of yet further discrepancies and disharmonies between our intentions, as based on these meanings, and the actual consequences that flow out of these intentions. At any stage the perception of new meanings .may

dissolve these discrepancies, but there will still continue to be a limit, so that the resulting knowledge is still incomplete.

What this implies is that meaning is capable of an indefinite extension to ever greater levels of subtlety as well as of comprehensiveness — in which there is a movement from the explicate toward the implicate. This can only take place however when new meanings are being perceived freshly from moment to moment. But if significance comes solely from memory and not from fresh perceptions it will be limited to some finite depth of subtlety and inwardness.

Memory, being some kind of recording, necessarily has a certain stable quality which cannot transform its structure in any fundamental way, and has only a limited capacity to adapt to new situations — for example, by forming new combinations of known principles, either through chance or through rules already established in memory. Memory is thus necessarily bounded both in scope and in the subtlety of its content. Any structure arising solely out of memory will be finite, and will be able to deal with some finite limited domain; but of course, to go beyond this, a fresh perception of new meanings is needed. And in fact, when you have a fresh perception you may also see new meanings of your memories. In other words, memory may cease to be so limited when there is fresh perception. To go on in this way to new meanings that are not arbitrarily limited requires a potentially infinite degree of inwardness and subtlety in our mental processes. And I am suggesting that these processes have access to an, in principle, unlimited depth in the implicate order.

Thus far I have suggested reasons why meaning is capable of infinite extension to ever greater levels of subtlety and refinement. However, it might seem at first sight that in the other direction -of the manifest and the somatic — there is a clear possibility of a limit in the sense that one might arrive at a “bottom level” of reality. This could be, for example, some set of elementary particles out of which everything would be constituted such as quarks, or perhaps yet smaller particles. Or in accordance with currently accepted views of modern physics it might be a fundamental field, or set of fields, that was the “bottom level.” What is of crucial importance is that its meaning would be in principle unambiguous. In contrast, all higher order forms in this supposedly basic structure of matter are ambiguous — that is, their meaning is incomplete. There is an inherent ambiguity in any concrete meaning.

That is to say, how the meanings arise and what they signify depends to a large extent on what a given situation means to us, and this may vary according to our interests and motivations, our background of knowledge, and so on. But if for example, there were a “bottom level” of reality, these meanings would be exactly what they were, and anybody who looked correctly could find them. They would be a reality that was just simply there, independent of what it meant to us.

Of course you also have to keep in mind that all scientific knowledge is limited and provisional so that we cannot be certain that what we think is the “bottom level” is actually so. For example, possibly something other than the present theories will come to reveal a “bottom level.” But this uncertainty of knowledge cannot of itself prevent us from believing in the existence of some kind of “bottom level” if we wish to do so. It is not commonly realized however that the quantum theory implies that no such “bottom level” of unambiguous reality is possible.

Now this is a bit difficult to make clear in this short time, but Niels Bohr, one of the founders of modern physics, has made one of the most consistent interpretations of the quantum theory given thus far, and which has been accepted by most physicists (though few probably have studied it deeply enough to appreciate fully the revolutionary implications of what he has done). To understand this point, first we have to say that while the quantum theory contradicts the previously existent classical theory, it does not explain this theory’s basic concepts as an approximation or a simplification of itself, but it has to presuppose the classical concepts at the same time that it has to contradict them. The paradox is resolved in Bohr’s point of view by saying that the quantum theory introduces no new basic concepts at all. Rather what it does is to require that concepts such as position and momentum, which are in principle unambiguous in classical physics, must become ambiguous in quantum mechanics. But ambiguity is just a lack of well-defined meaning. So Bohr, at least tacitly, brings in the notion of meaning as crucial to the understanding of the content of the theory.

Now this is a radically new step, and he is doing this not just for its own sake, but he is forced to do something like this by the very form of the mathematics which so successfully predict the quantum properties of matter. This mathematics gives only statistical predictions. It not only fails to predict what will happen in a single measurement, it cannot even provide an unambiguous concept or picture of what sort of process is supposed to take place. So for Bohr the concepts are ambiguous, and the meaning of the concepts depends on the whole context of the experimental arrangement.

The meaning of the result depends on the large scale behaviour which was supposed to be explained by the particles themselves. So in some sense you do not have a “bottom level” but rather you find that, to a certain extent, the meaning of these particles has the same sort of ambiguity that we find in mental phenomena when we are looking at meaning.

This kind of situation is what is pervasively characteristic of mind and meaning. Indeed the whole field of meaning can be described as subject to a distinction between content and context which is similar to that between soma and significance, and between subtle and manifest.

Content and context are two aspects that are inevitably present in any attempt to discuss the meaning of a given situation. According to the dictionary, the content is the essential meaning – for example, the content of a book. But any specifiable content is abstracted from a wider context which is so closely connected with the content that the meaning of the former is not properly defined without the latter. However, the wider context may in turn be treated as a content in a yet broader context, and so on. The significance of any particular level of content is therefore critically dependent on its appropriate context, which may include indefinitely higher and more subtle levels of meaning – such as whether a given form seen in the night means a shadow or an assailant depends on what one has heard about prowlers, what one has had to eat and drink, and so on. So you see, this sort of context-dependence is just what is found in physics with regard to matter, as well as in considerations of mind or meaning.

Now I believe Bohr’s interpretation of quantum theory is consistent, and he has produced a very deep insight at this point; but it is still not clear why matter should have this context-dependence. He just says that the quantum theory gives rise to it.

However, in terms of the implicate order, an alternative interpretation is possible in which one can ascribe to phenomena a deeper reality unfolding, which gives rise to them. This reality is not mechanical; rather its basic action and structure are understood through enfoldment and unfoldment. What is important here is that the law of the total implicate order determines certain sub-wholes which may be abstracted from it as having relative independence. The crucial point is that the activity of these sub-wholes is context-dependent, so that the larger content can organize the smaller context into one greater whole. The sub-wholes will then cease to be properly abstractable as independent and autonomous. The implicate order makes it possible to discuss the notion of reality in a way that does not require us to bring in the measuring apparatus, which Bohr does. He makes the context very much dependent on the apparatus; but he does so by making nature generally context-dependent. That is to say, the situation of any part of nature is context-dependent in a way that is similar to the way that meaning is dependent on its context – that is, as far as the laws of physics are concerned.

That would suggest that in a natural way one might extend some notion similar to meaning to the whole universe. It is implied that each feature of the universe is not only context-dependent fundamentally, but also that the grosser, manifest features depend on the subtler aspects in a way that is very analogous to soma-significant and signa-somatic activity. So something similar to meaning is to be found even in the somatic or physical side.

Now as I said, this holds for us both mentally and physically. It would suggest that everything, including ourselves, is a generalized kind of meaning. Now I am not thereby attributing consciousness to nature. You see, the meaning of the word “consciousness” is not terribly clear. In fact, without meaning I think that there would be no consciousness. The most essential feature of consciousness is consciousness of meaning. Consciousness is its content; its content is the meaning.

Therefore it might be better to focus on meaning rather than consciousness. So I am not attributing consciousness as we know it to nature, but you might say that everything has a kind of mental side, rather like the magnetic poles. In inanimate matter the mental side is very small, but as we go deeper into things the mental side becomes more and more significant.

All of this implies that one can consistently understand the whole of nature in terms of a generalized kind of soma-significant and signa-somatic activity that is essentially independent of man, and that indeed it is more consistent to do this than to suppose that there is an unambiguous “bottom level” at which these considerations have no place. I would say that the crucial difference between this and a machine is that nature is infinite in its potential depths of subtlety and inwardness, while a machine is not. Although to a certain extent, a machine such as a computer has something similar. So it is in principle possible in this view to encompass both the outward universe of matter and the inward universe of mind.

In this approach, the three basic aspects arise:

Soma Significance Energy

To repeat, soma-significance means that the soma is significant to the higher or more subtle level. Signa-somatic means that that significance acts somatically toward a more manifest level.

Now I’m going to look at physical action in a similar way – to say that in the unfoldment of matter there is a kind of soma-significance; that the soma may be significant to a deeper level. So let’s say that something unfolds and has a significance, and as a result something else unfolds.

In explaining this I should first discuss the work of the well-known psychologist Piaget, who has carefully observed and studied the growth of intelligent perception in infants and in young children. This led him to say that this perception flows out of what is in effect a deep initial intention to act toward the object. You can see the soma-significance coming in here. This action may initially be based partly on a kind of significance that objects have, which is grounded in the whole accumulated instinctive response to the experience of the species, and partly on a kind of significance that is grounded in his own past experience.

Whatever its origin may be, Piaget says, what this action does is to incorporate or assimilate its object into a cycle of inward and outward activity. He moves out, he sees it, he acts on it and that changes his perception, and he acts again. His intention is implicitly in at least some conformity with what he expects the object to be, but it might be vague. The action comes back to the extent to which the object fits or doesn’t fit his intention. Then this brings about a modified intention with correspondingly modified outward action. This process is continued until a satisfactory fit is obtained between intentions and their consequences, after which it may remain very stable until further discrepancies appear.

Piaget points out, however, that the initial intention need not be directed primarily toward incorporating the object into a cycle of activity in order to produce a desired result such as enjoyment or satisfaction. Instead it might be directed mainly at perception of the object.

For example, the child may initiate movements aimed at exploring and observing the object, such as turning it around, bringing it closer to look at it, and so on. From such an intention it is possible for him to begin with all sorts of provisional feelings as to what the object might be, and to allow these to unfold into actions which come back as perceptions of fitting or non-fitting. This leads to a corresponding modification of the detailed content of the intention behind these movements until the outgoing actions and incoming perceptions are in accord. This is a very important development of intentional activity which makes possible an unending movement of learning and discovering what has not been known before. So we want to say that this soma-significant and signa-somatic activity, constantly going back and forth, is what is involved in learning. And we can say that this is going on, not only in regard to outward objects, but inwardly — that is, for example, with regard to thought. And there may be another level which picks up the meaning of the thought and takes an action toward that thought while thinking another thought to see if it is consistent.

If it is not, then the intention changes until we get a consistent relationship between the thought which arises from the deeper intention and the thought that was first being looked at. You see, you may have a thought that you want to look at, and there may be a deeper intelligence which is able

to grasp the meaning of that thought in a broader context and take an action toward it by, as it were, thinking again and seeing whether the thought which comes out is coherent with the thought with which you started. And if it’s not, then you can start to change that action until it is. Or you can change the thought. Change can occur at various levels.

So all of these levels of meaning enfold each other and have a certain bearing on each other. This whole process is always soma-significant and signa-somatic, going to ever deeper levels. When I talk of these processes I don’t only mean going outward into the manifest world, but also the deeper mental processes being explored by still more subtle mental processes. So you could say that the mind has available in principle an unlimited depth of subtlety, and learning can take place at all these levels.

Now what is important is not only what to think but how to think. But if we ask how we think, it may be just as difficult to answer as, how do you ride a bicycle? It is at the tacit level of knowing, or at the subtle level, that how to think takes place. You cannot say how to think but you can learn, as I have just been describing, through signa-somatic and soma-significant activity.

To sum up what I’ve just been saying, a somewhat similar view can be applied within matter in general. So one may think of the whole thing as one process – as an extended idea of meaning and an extended idea of soma. That is, meaning and matter may not have the same sort of consciousness that we have, but there is still a mental pole at every level of matter, and there is some kind of soma-significance. And eventually, if you go to infinite depths of matter, we may reach something very close to what you reach in the depths of mind. So if you consider it, we no longer have this division between mind and matter.

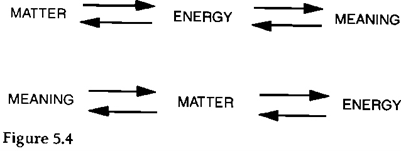

Now we have in this whole process these three aspects: soma and significance and an energy which carries the significance of soma to a subtler level and gives rise to a backward movement in which the significance acts on the soma. Modern physics has already shown that matter and energy are two aspects of one reality. Energy acts within matter, and even further, energy and matter can be converted into each other, as we all know.

From the point of view of the implicate order, energy and matter are imbued with a certain kind of significance which gives form to their over-all activity and to the matter which arises in that activity. The energy of mind and of the material substance of the brain are also imbued with a kind of significance which gives form to their over-aU activity. So quite generaUy, energy enfolds matter and meaning, while matter enfolds energy and meaning.

You can see in Figure 5.4 how the middle term enfolds the other two.

But also meaning enfolds both matter and energy. The way we find out about matter and energy is by seeing what they mean (see Figure 5.5).

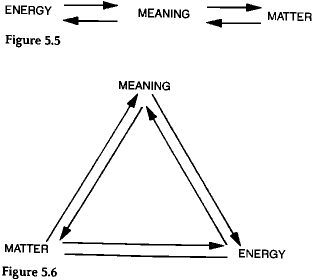

So each of these basic notions enfolds the other two. It is through this mutual enfoldment that the whole notion obtains unity. So we can put all these relationships together (see Figure 5.6).

However in some sense the enfoldment by meaning seems to be more fundamental than the enfoldment of the other types, because we can discuss the meanings of meaning. In some sense meanings enfold meanings. But we cannot have the matter of matter, or the energy of energy. There seems to be no intrinsic enfoldment relation in matter-energy. Matter enfolds energy, and energy enfolds matter, according to this view, by way of significance. But meaning refers to itself directly, and this is in fact the basis of the possibility of that intelligence which can comprehend the whole, including itself. On the other hand, matter and energy obtain their self-reference only indirectly, firstly through meaning. That is, we can refer matter back to itself by first seeing what it means to us, and then going back. Or we can refer matter to energy, or energy to matter, by seeing what they mean. We refer them to each other reflexively, but only through their meaning.

Generally we have this problem of thought referring to something else, thus creating division and dualism. Even the thought that the universe is one unbroken whole in flowing movement refers to a universe which is one whole unbroken movement, and beside that there is the thought. So we therefore have two nevertheless. What we would like is a view in which the thought itself is part of the reality.

Usually we think of thought in correspondence with some object; the features of the thought correspond to some object. But as soon as you say a thought corresponds to an object, you immediately have, tacitly, a division between the object and the thought. In reality, we are saying that the thought is a part of the soma-significance and cannot be absolutely distinct from the object. Only in certain limited areas is the distinction useful or correct — that is, where the thought has a negligible effect on the object. This is the area of all practical activity, technology, and so on.

The modern mechanistic approach says that this area covers everything: but what I am saying is that it is a small area within a much vaster field. So we are not denying that kind of thought; we are saying it is only valid in a limited area.

The problem of conceiving of a universe that can refer consistently to itself has long been a difficult one that has not been resolved in a really adequate way. But the field of meaning can refer to itself, and of course, it also presupposes the context of the universe to which it also refers.

Meaning, though, has nevertheless been regarded as peculiar to our own minds and not as a proper part or aspect of the objective universe. However if there is a generalized kind of meaning intrinsic to the universe, including our own bodies and minds, then the way may be opened to understanding the whole as self-referential through its “meaning for itself” — in other words, by whatever reality is. And the universe as we now conceive it may not be the whole thing.

The aspect of soma cannot be divided from the aspect of significance. Whatever meanings there may be “in our minds,” these are, as we have seen, inseparable from the totality of our somatic structures and therefore from what we are. So what we are depends crucially on the total set of meanings that operates “within us.” Any fundamental change in meaning is a change in being for us. Therefore any transformation of consciousness must be a transformation of meaning.

Consciousness is its content — that is its meaning. In a way, we could say that we are the totality of our meanings.

If we trace some of these meanings to their origins, we find that most of them have come from society as a whole. Each person takes up his own particular combination of the general mixture that is available in a society. And so at least in this way, every person is different. Yet the underlying basis is characterized mainly by the fundamental similarity over the whole of mankind, while the differences are relatively secondary. And insofar as man has the capacity to get beyond that, that also is common.

These meanings change as human beings live, work, communicate and interact. These changes are based for the most part on adaptation of existent meanings. But it has also been possible from time to time for new meanings to be perceived and realized — in other words, made real. Perceptions of this kind have generally occurred when someone became aware that certain sets of older meanings

no longer made any sense. This may be understood as a vast extension of what happens in the development of intelligence in young children. That is, as they see something about which they are puzzled, they have to see its meaning in a new way.

Now we can say that we are puzzled about the whole of life, and we have to see it with a new meaning. If you look at life as a whole it doesn’t seem to make that much sense — the way we live, and so on. The childlike attitude would ask, “Well, what does it mean?” And some as yet incompletely formed notion of a new meaning that removes the contradictions in the older meanings may begin to penetrate a person’s intentions. As I explained, the actions unfolding from the intentions would be displayed, for example, in the imagination, and the discrepancies between what is displayed and what is intended would lead to a change of intention aimed at decreasing this discrepancy, and so on. In this way a greater clarification of the meaning would occur along with a possibility of realizing it through a change in intention, because it is only when one’s purpose or intention changes that a new meaning can be realized. Then, often in a flash that seems to take no time at all, a coherent new whole of meaning is formed, within which the older meanings may be comprehended as having a limited validity within their proper context.

Now if meaning is an intrinsic part of not only our reality but reality in general, then I would say that a perception of a new meaning constitutes a creative act. As their implications are unfolded, when people take them up, work with them, and so on, the new meanings that have been created make their corresponding contributions to this reality. And these are not only in the aspect of significance but also in the aspect of soma. That is, the situation changes physically as well as mentally.

Therefore each perception of a new meaning by human beings actually changes the over-all reality in which we live and have our existence — sometimes in a far-reaching way. This implies that this reality is never complete. In the older view, however, meaning and reality were sharply separated. Reality was not supposed to be changed directly by perception of a new meaning. Rather it was thought that to do this was merely to obtain a better “view” of reality that was independent of what it meant to us, and then to do something about it. But once you actually see the new meaning and take hold of your intention, reality has changed. No further act is needed.

Seeing something intellectually or abstractly, though, will not change your intention. You may say that you need an act of will to change it, but I think that when you really see something deeply with great energy, no further act of will is needed. If you really see a new meaning to be true, then your intention will change — unless there is something blocking it, such as your conditioning, or the “program.” And if something is blocking it, then the will is not going to help, because you don’t know what the block is. Therefore you have to see the meaning of the block. So choice and will are of limited significance — valid in certain areas. But I think something deeper is needed if you are discussing the transformation of mind or consciousness or matter — they really all change together.

You see, the deep change of meaning is a change in the deep material structure of the brain as well, and this unfolds into further changes. Every time you think, the blood distribution all over the brain changes; every emotion changes it. Between thinking and the somatic activity there is also a tremendous connection with the heartbeat and the chemical constitution of the blood, and so on.

The new meaning will produce different thought and therefore possibly an entirely different functioning of the brain.

We already know that certain meanings can greatly disturb the brain, but other meanings may organize it in new ways. And when the brain comes to a new state, new ideas become possible. But the new meaning is what organizes the new state. If the brain holds the old meanings, then it cannot change its state. The mental and the physical are one. A change in the mental is a change in the physical, and a change in the physical is a change in the mental. In fact, there has been some discussion of what is called subtle brain damage in animals in which no physical abnormality can be found; but some disturbance of function takes place when the animals are put under stress. So you see, we could say that living as we do, we probably have a great deal of subtle brain damage.

In other words, the brain is damaged at a subtle level that might not show up at the cellular level, but deep in the implicate order. So instead of saying that when we see a new meaning we make a choice and then act, we say that the perception and realization of the new meaning in our intention is already the change.

This point is crucially significant for understanding psychological and social change. For if meaning is something separate from human reality, then any change must be produced by an act of will or choice, guided perhaps by our new perception of meaning. But if meaning itself is a key part of reality, then once society, the individual and their relationships are seen to mean something different from what they did before, a fundamental change has already taken place. So social change requires a different, socially accepted meaning, such as in the change from feudalism to the forms that followed it, or from autocracy to democracy, or to communism, and so on. According to the meanings accepted, the entire society went.

These meanings may have been correct or incorrect. But once the meanings become fixed, the whole thing must gradually go wrong. Or to put it differently, what man does is an inevitable signa¬somatic consequence of what the whole of his experience, inward and outward, means to him. For example, once the world came to mean a set of disjointed mechanical fragments, one of which was himself, people could not do other than begin to act accordingly and engage in the kind of ceaseless conflict that this meaning implies. The meaning of fragmentation includes conflict and self-centredness — in other words, not creative tension but meaningless conflict.

However if mankind could sustain a perception and realize this perception signifying that the world is an unbroken whole with a multiplicity of meanings, some of which are fitting and harmonious and some of which are not, a very different state of affairs could unfold. For then there could be an unending creative perception of new meanings that encompass the older ones in broader and more harmonious wholes which would unfold in a corresponding transformation of the over-all reality that was thus encompassed.

Here it is worth noting that our civilization has been suffering from what may be called a failure of meaning. Indeed from earliest times people have felt this as a kind of” meaninglessness” of life.

Whether this is more prevalent today, I don’t know, but people say it is. But in this sense, meaning also signifies value. That is to say, a meaningless life has no value; it is not worth living. But of course it is impossible for anything to be totally free of meaning. For as we have explained earlier,

the notion of generalized soma-significance, regarded as valid for the whole of life, implies that each thing is its total meaning — which of course must include all of its relevant context. What I intend by “meaningless” therefore is that there is a meaning, but that it is inadequate because it is mechanical and constraining and is hence of little value and not creative. A change in this is possible only if new meaning is perceived that is not mechanical. Such a new meaning, sensed to have a high value, will arouse the energy needed to bring a whole new way of life into being. You see, only meaning can arouse energy.

At present people don’t seem to have the energy to face this sea of troubles that threatens to overwhelm us, generally speaking. If we take a mechanical meaning, it tends to deaden the energy so that people remain indefinitely as they have been, or at best allows change in limited directions, such as the continuation of the development of technology, and so on. So I am saying that meaning is fundamental to what life actually is.

Now you can extend this to the cosmos as a whole. We can say that human meanings make a contribution to the cosmos, but we can also say that the cosmos may be ordered according to a kind of “objective” meaning. New meanings may emerge in this over-all order. That is, we may say that meaning penetrates the cosmos, or even what is beyond the cosmos. For example, there are current theories in physics and cosmology that imply that the universe emerged from the “big bang.” In the earliest phase there were no electrons, protons, neutrons, or other basic structures. None of the laws that we know would have had any meaning. Even space and time in their present, well-defined forms would have had no meaning. All of this emerged from a very different state of affairs. The proposal is that, as happens with human beings, this emergence included a creative unfoldment of generalized meaning.

Later, with the evolution of new forms of life, fundamentally new steps may have evolved in the creative unfoldment of further meanings. That is, we may say that some evolutionary processes occur which could be traced physically, but we cannot really understand them without looking at some deeper meaning which was responsible for the changes. The present view of the changes is that they were random, with selection of those traits that were suited for survival, but that does not explain the complex, subtle structures that actually occurred.

The question is how our own meanings are related to those of the universe as a whole. We could say that our action toward the whole universe is a result of what it means to us. Now since we are saying that everything acts according to a similar principle, we can say that the rest of the universe acts signa-somatically to us according to what we mean to it.

These meanings do not all fit harmoniously, but if we are perceptive of the disharmony, we may continually be bringing about an increase in harmony. That is to say, there is no final meaning or no final harmony, but a continual movement of creativity – or of destruction. In the long run, only those meanings which allow changes that tend to bring about accord between us and the rest of the universe will be possible. We can say that that is true for the universe as a whole, and that nature is experimenting with all sorts of meanings. Some of them will not be consistent, and they will not survive. So anything that has survived for quite a long time is bound to have a tremendous degree of coherence with the rest of the universe.

We are proposing that this holds for both living beings and for matter in general. We may say then that the harmony is never complete and cannot be so. Even now a further creation of meaning is going on in a process that includes mankind as part of itself. Not merely man’s physical development but a constant creation of new meanings that is essential for the unfoldment of society and human nature itself. Even time and space are part of the total meaning and are subject to a continual evolution. As I indicated, at the beginning of the “big bang,” time and space did not mean what they now mean. In this evolution, extended meaning as “intention” is the ultimate source of cause and effect, and more generally, of necessity – that which cannot be otherwise.

Rather than to ask what is the meaning of this universe, we would have to say that the universe is its meaning. As this changes, the universe changes along with all that is in it. What I mean by “the universe” is “the whole of reality” and what is beyond. And of course, we are referring not just to the meaning of the universe for us, but its meaning “for itself,” or the meaning of the whole for itself.

Similarly there is no point in asking the meaning of life, as life too is its meaning, which is self-referential and capable of changing, basically, when this meaning changes through a creative perception of a new and more encompassing meaning.

You could also ask another question: What is the meaning of creativity itself? But as with all other fundamental questions we cannot give a final answer, but we have to constantly see afresh. For the present we can say that creativity is not only the fresh perception of new meanings, and the ultimate unfoldment of this perception within the manifest and the somatic, but I would say that it is ultimately the action of the infinite in the sphere of the finite – that is, this meaning goes to infinite depths.

What is finite is, of course, limited. These limits may be extended in any number of ways, but however far you go, they are still limited. What is limited in this way is not true creativity. At most it leads to a kind of mechanical rearrangement of the kinds of elements and constituents that are possible within those limits. One may think of anything finite as being suspended in a kind of deeper infinite context or background. Therefore the finite must ultimately be dependent on the infinite. And if it is open to the infinite then creativity can take place within it. So the infinite does not exclude the finite, but enfolds within it and includes and overlaps it. Every finite form is somewhat ambiguous because it depends on its context. This context goes on beyond all limits, and that is why creativity is possible. Things are never exactly what they mean; there is always some ambiguity